Riding Gaited Equine by Terry Ann Frick

by Terry Ann Frick

Illustrations by Lanie Frick

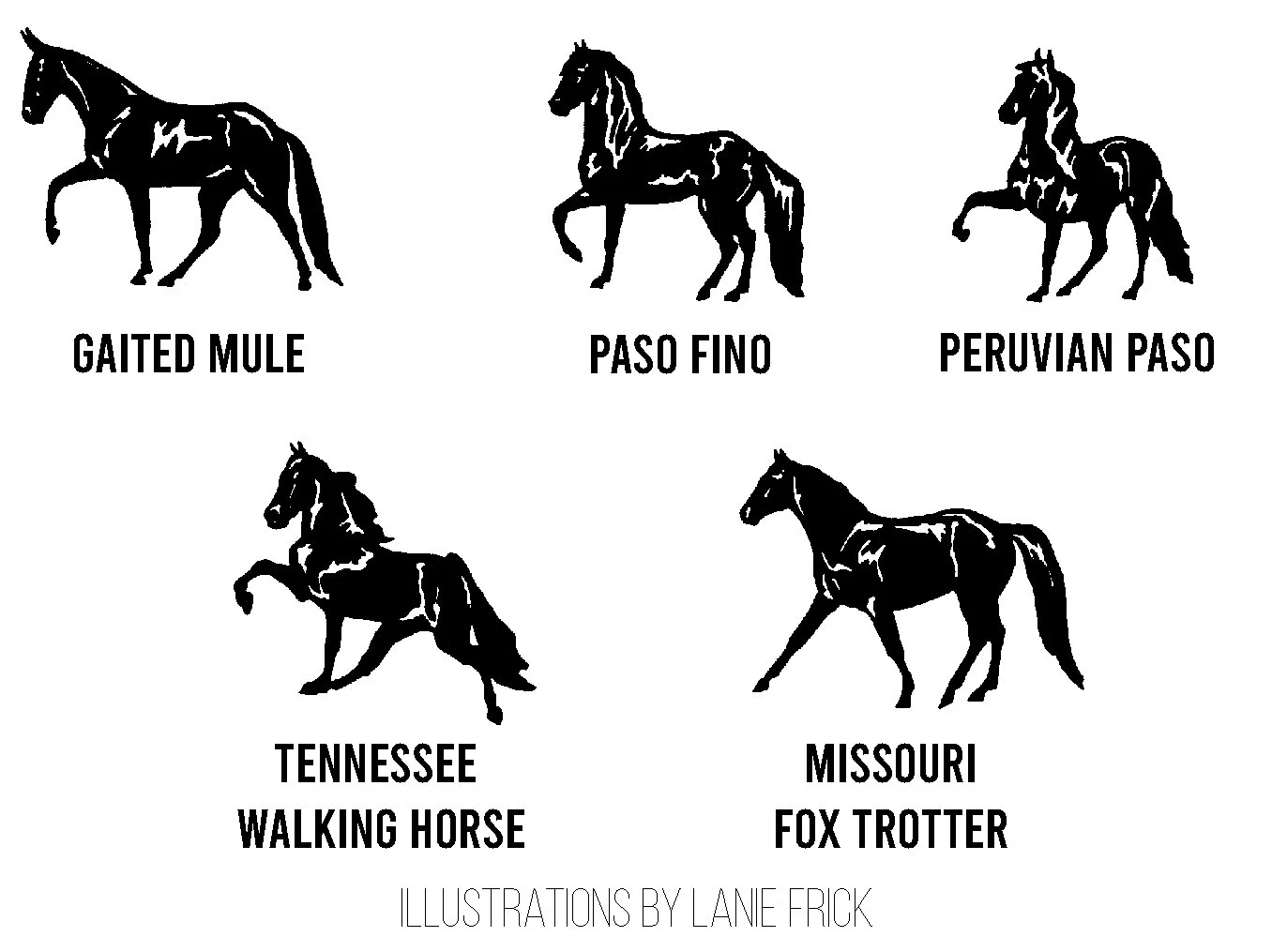

I grew up in a horse-oriented family that has consistently ridden both three-gaited and “gaited” horses. All gaited horse breeds except one can walk, trot, canter, AND travel in a four-beat lateral gait. The one breed exception is the Missouri Fox Trotter, whose additional gait is a four-beat diagonal pattern. Each horse’s gaiting ability results from and is facilitated by conformation attributes, which are specific to gaiting:

• The neck naturally rises from the withers at a higher angle than that of the typical three-gaited horse.

• When collected and on-the-bit in gait, the horse’s back rises, but does not become convex like that of a three-gaited horse who is collected and on-the-bit.

A three-gaited horse can walk, trot, and canter, whether or not his hindquarters are truly engaged, but to initiate and/or stay in gait, the gaited horse must be able to drop his hindquarters, drive his motion forward from the rear, and elevate his withers. To assist the horse in generating and maintaining this motion, some gaited-horse riders lean decidedly backwards and push their legs and feet well out in the horse to gait (while leaning forward in the saddle prohibits the horse’s gait), but does not promote the horse’s ability to gait his best.

There are certain universal principles which apply to riding a horse, regardless his breeding, his gaits, and our choice of discipline and tack. When we understand and use these principles, we are:

• Centered and balanced on the horse, which allows the horse to balance himself and carry himself to the best of his ability in any gait.

• Supple in the saddle and without tension, allowing us to respond to any move the horse makes without being jerked back and forth and without fear of falling off.

• Able to feel the horse’s motion and thus be in a position to promptly and correctly adjust our cues.

The generally seen and accepted position for riding a gaited horse is diametrically opposed to accomplishing any of the above. Pushing your legs and feet out in front of you constricts your hip sockets, precluding suppleness. That, combined with the use of the stirrups, can create tension in your ankles and thus the rest of your body. While leaning back takes weight off the horse’s shoulders and allows him to lift his withers, leaning too far back shifts your weight out of the best position for enabling the horse to easily balance himself.

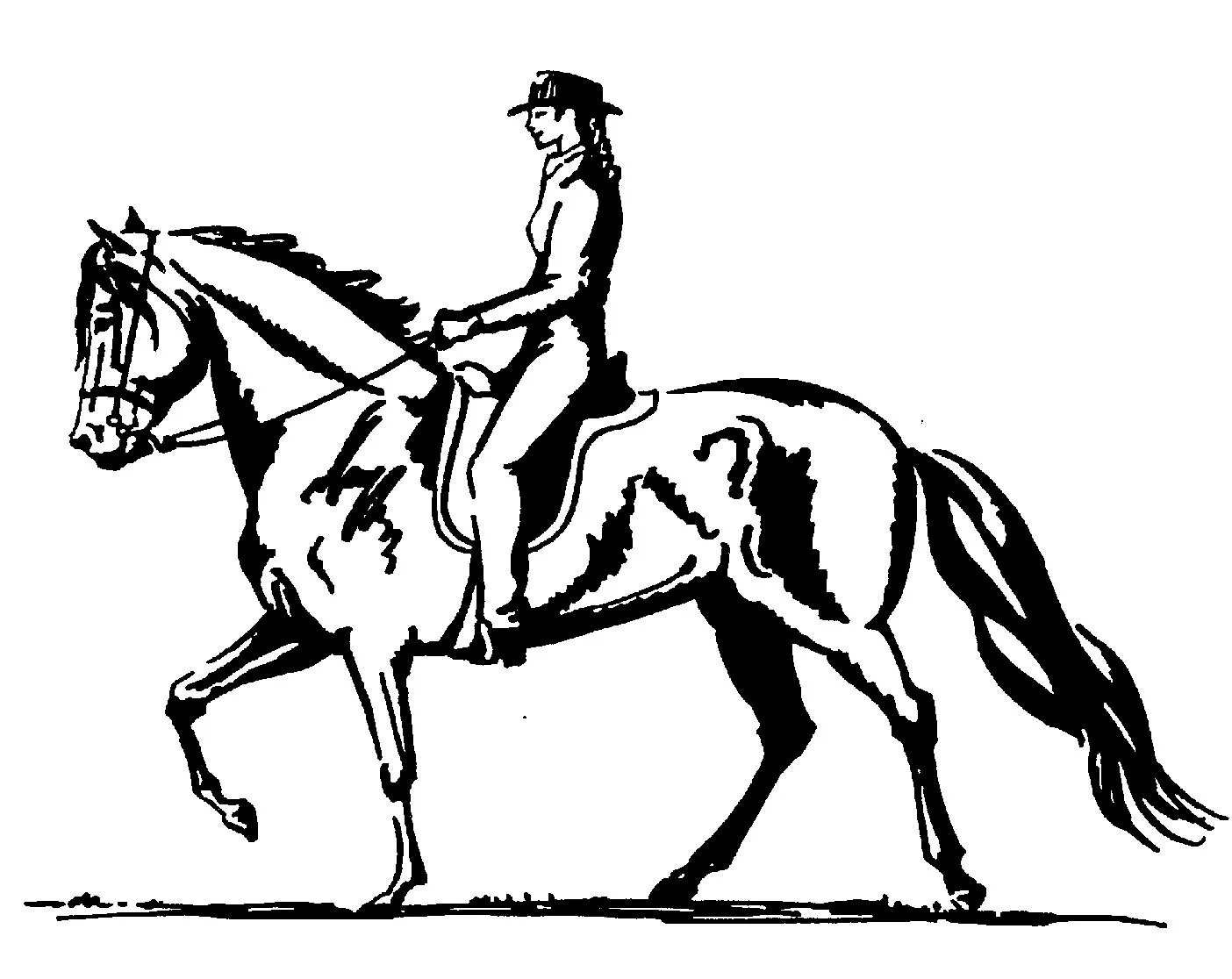

The balance position for a three-gaited horse requires the rider’s head, shoulders, hips, and heels to be in true vertical alignment. The accompanying illustration depicts the balance position for riding a gaited horse. The gaited horse does require the rider to very slightly shift the rider’s back behind vertical and to slightly shift the rider’s feet in front of vertical. But this position is dramatically different from the “rocking chair” seat adopted by many gaited-horse riders.

The gaited-horse balance position (combined with tension-free, supple muscles) achieves the most critical measure by which gaited horses, whatever breed, are judged: A truly fluid and consistent gait. The result is a horse who performs at his optimum -- gaiting freely, willingly and virtually effortless -- as if he were doing so without a rider.