Trail Success Begins with the Basics, by Susan Dudasik

by Susan Dudasik, Salmon, ID

WHEN INTRODUCING YOUR MULE to a new object, allow him to get a really good look and smell. Give him time to investigate

From the December 1999 Issue

It takes lots of time, patience and understanding to train a top trail mule. Whether its job is competitive pleasure riding or competing in trail class events, a well trained mule must have a firm foundation in basic ground training. Unfortunately many folks are too eager to ride their mule and overlook this basic, continuous training. If they can drag their mule into the trailer and force it past spookie objects, they are content, but they don’t have a real partnership with their mule, just a domineering position. There is a difference. To establish a good partnership with a mule of any age takes time and understanding.

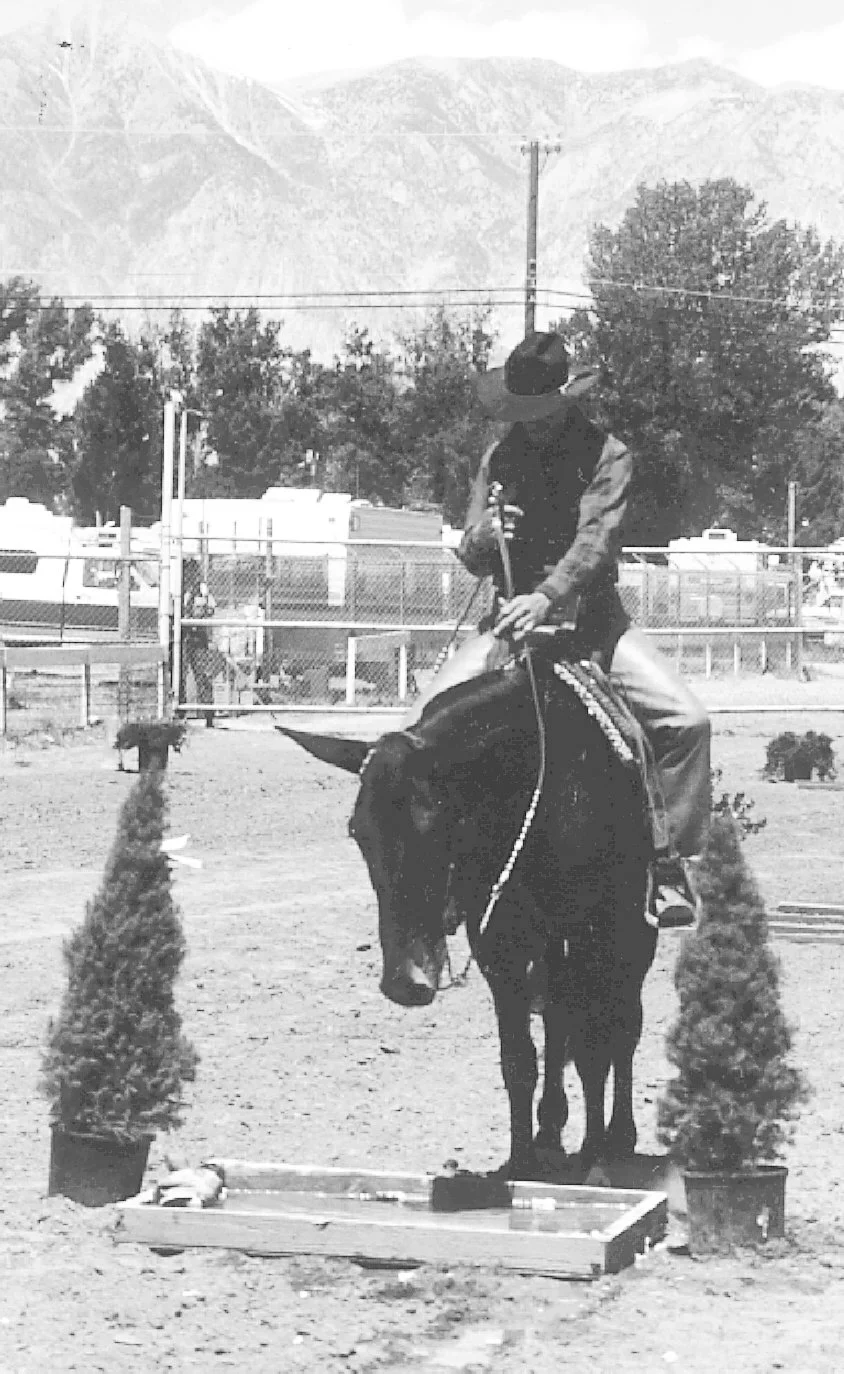

TO SUCCEED IN WORKING an obstacle like this one takes patience and understanding on the rider’s part. By allowing your mule to investigate spookie objects, instead of forcing him over them, he will become more trusting and willing to try new things

So what makes a successful trail mule? Aside from being able to walk, trot, lope, stop and back up, a good trail mule should also be proficient at side-passing, turning on the haunches and forehand, and confidently negotiating a variety of obstacles. However, one of the biggest misconceptions people have toward trail training is that the main emphasis is on working obstacles. In fact the success begins long before the first obstacle is approached. It starts when the mule is taught or retaught to lead. To do anything, there must be forward motion. Without it, you can’t get anywhere, not even out of the stall. Basically all training requires forward motion, even backing-up. A mule that pulls back or refuses to go forward is dangerous; the next step is rearing.

Most successful trail mules are started on the ground and have strong basic ground manners. They are well “halter-broke”, meaning they will not pull against their halter and will lead anywhere as well as stand tied and trot in hand. There are many mules that can be ridden over an obstacle but not lead over it. Just because a mule will do something under saddle doesn’t mean he’s halter-broke. Mules that refuse to trailer load are often poorly halter-broke.

There are two simple tests you can use to determine how well halter-broke your mule is. The first is to simply lead him a short distance then ask him to stand for about three minutes. He should quietly stand about a foot and a half from you without tossing his head, dancing around, pawing or using you as a scratching post. A mule that does any of these things lacks respect and confidence in its handler, two major ingredients needed to create a top trail team.

The second test is to take him for a walk around the barn. Lead him up to a plastic milk jug tied to a hitch rail or other “spookie” objects. Walk through a mud puddle, step over some logs, lead him through a gate, walk over a tarp or piece of plywood and back him in hand about 10 feet. If your mule has done most of these without pulling back, rushing forward or crowding you, congratulations! If you have instilled enough trust in your mule that he will allow you to lead him up to something that frightens him, you have won three-fourths of the battle. If he’s done any of the aforementioned things, you have lots of work to do.

NOTICE THE BODY LANGUAGE..... This young mule is not happy about being near the barrel, but because he has confidence in his handler, he came near it instead of lagging back

Creating a top trail team requires confidence between mule and rider. The mule must accept you as leader and be willing to follow your command even when his good sense tells him not to. Why walk over a tarp when there is solid ground all around it? Or walk through a puddle when he can go around or jump it? Most moves required to succeed in trail are learned. It’s rare to see a loose mule turning on the haunches, backing up or sidepassing, unless he has been taught to do so. All of these moves can be taught from the ground. Whether the mule is six months old or 16 years old, it just takes patience, repetition and communication.

The best way to learn about your mule is to observe him when he’s turned loose. Place him in a small corral and put a coat, sack of cans or some other object in with him. Sit back and watch. Most often he will walk around the object, observing it from all directions. then he will walk toward it then back off. Next he’ll move a bit closer, sniff and back off. This will keep up until he finally touches it. Most likely he will touch it, back off, then come back and touch it again. This is his nature and the method you want to use in your training. The goal is to have the mule willing to approach and accept things.

Now, armed with treats or carrot slices, take your mule back to what he spooked from. Let’s say he wouldn’t go up to the milk jug on the rail. Walk him toward it until he starts to spook. Talk to him and encourage him forward. If he sticks his nose out or steps forward, stop and pet him. Give him a treat. When he relaxes, ask for another step forward. When he responds, pet him. Keep repeating this until he is near the jug. It may take two minutes to an hour but stick with it. Ignore those telling you to “swat him on the butt or to drag him to it.” This will just create a vicious cycle of fear. Establishing trust and respect takes time but will pay off in the long run. When he’s standing next to the jug, encourage him to touch it. Start establishing a cue word such as “touch it” or “smell it”. Be prepared, he will probably touch it and instantly pull back. Praise him and try again. Allow him to back up but bring him right back and have him touch it again. Offer a treat and praise when he does. Before long he will realize there is nothing to be afraid of and he wasn’t scolded for his fear. You have given him time to figure out, on his own, that the jug wasn’t going to eat him and you weren’t yelling or hitting him for his fears.

By using this method of advance and retreat, you can introduce your mule from the ground to a variety of trail objects such as a sack of cans set on top of a barrel, mailboxes, jackets tossed over rails, bridges and tarps. Observe any type of trail competition and you will soon notice that the biggest obstacle for many exhibitors is not the obstacle itself, but getting their mule to approach it in the first place. Here lies one of the secrets to a successful trail rider or competitor: trust between mule and rider that the rider would never ask the mule to do anything that will hurt either of them. And accomplishing that trust takes time and getting on the ground, back to the basics.