The Best Color of Jackstock

By Earl Sunderman, Villisca, Iowa

From the March 1997 issue of Mules and More

Texas Scooter

My involvement with jackstock and saddle mules over the past several years has taken me to many sales and mule shows. While attending these events, I have tried to gain some amount of knowledge about the type of jack that it takes to produce a winning show mule. Halter classes here in the Midwest have been dominated for the past several years by the mules sired by an old jack called Texas Scooter and his sons. This bloodline has been a sure enough producer of the halter kind. Halter classes are an important part of any mule show, but as I look back, I can recall some excellent performance mules as well. In fact, my fondest memories of past mule shows are not of halter winners, but rather the top game mules. It makes little difference how good a mule looks when this pretty mule has no other talent. The best mules are a combination of both looks and talent. I have had the opportunity to see a few of these. Some months back, I did a story for Mules and More about the versatility of DeWayne Cason's mule Skippy. Skippy halters, races, pleasures, games, and does cattle work. She does all of these things and does them well.

Another great mule that comes to mind as I look back is Jake, a rather small bay jack mule. I would guess him to stand about 55 inches tall. He was shown and ridden by the Waddle family of Kirksville, Mo. At some of the first mule shows that I attended, Jake would be ridden as many as three or four times in the same event. Each time by a different Waddle. Jake could be counted on to carry multiple entrants in barrels, poles, hurdles, and whatever else the show offered. Not only was he entered a lot, but he won a lot. In his day, he was the mule to beat. He may not have been a consistent halter winner, but he sure looked good enough to win his share.

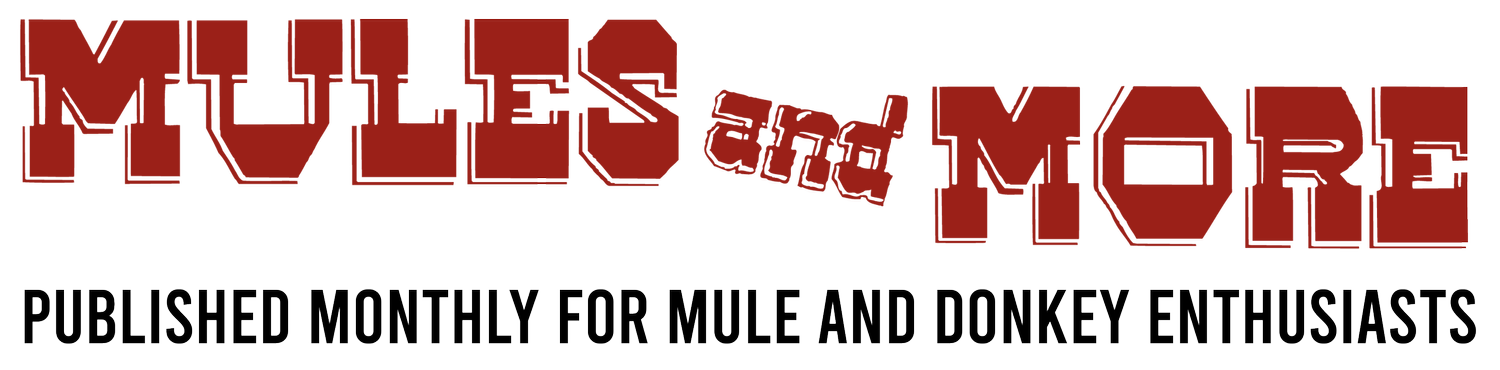

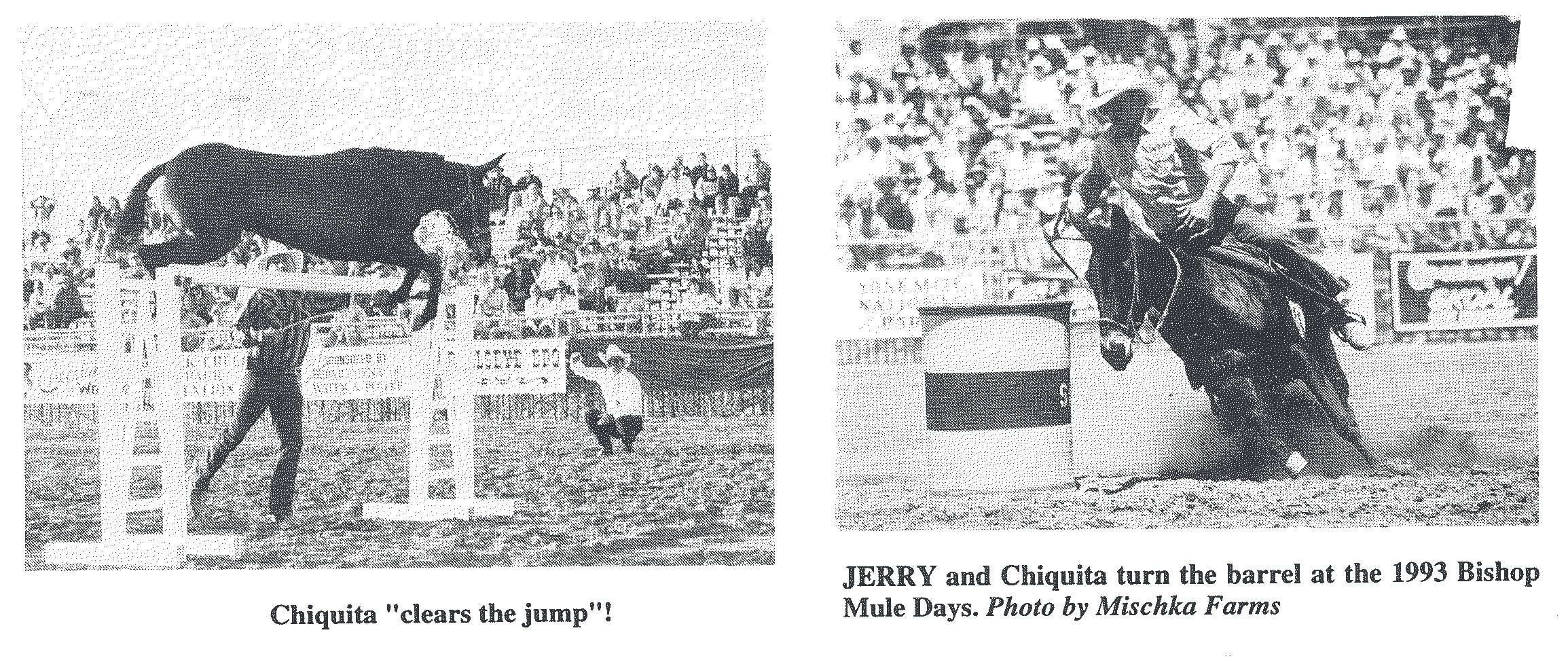

One of my all-time favorite mule shows was the one held at the Sidney, Iowa, rodeo grounds. It was managed by the local saddle club because several of its members were mule riders. I believe that Alfred Walker and Doug Blackburn were the mule men in charge of this show. This show was well attended by mules and their owners from at least four states, and it stands out in my mind because I had the opportunity and honor to observe Booger's Chiquita in action. Chiquita was owned and handled by the very capable Jerry Villines of Coffeyville, Kansas. In the speed events and games, she cleaned house. Chiquita would go on from there to become a many-time champion. At the big show in Bishop, Calif., she was truly a great one, and I'm glad that I had the chance to watch her perform before her untimely death. Mr. Villines told me that Chiquita was sired by a 47-inch black Spanish jack and out of a quarter mare. This is the lead in for my story on the best color of jackstock. These three great mules were sired by what the old timers call Spanish jacks.

In most cases, these so-called Spanish jacks, when not black, are endowed with a line down the back and a cross over the shoulder. I mention this because it would seem that no other color trait has been so rigorously selected against. In spite of the fact that nearly all jackstock breeders have avoided this color pattern, it still remains of value in the production of the modern saddle mule. In a recent telephone conversation with Jerry Villines, he told me he believed the Spanish jack was important in providing the heart and athletic ability in the saddle mule.

I wouldn't care to guess how many times I have been told by venerable old jack men that a stripe over the back is a sign of bad or inferior breeding. To this comment, I would ask, bad for what reason? Dr. Steve Aaron states in a recent issue of Mules and More, "Sooner or later those throwback stripes will come out, and they testify to burro origins." I can see a problem in this for the draft mule breeder, but not all jacks are used to produce draft mules. I have an old handbook published by The American Donkey and Mule Society and The Standard Jack and Jennet Registry that states, "Early breeders were completely against any gray-dun jack, as mules that followed this color in the jack, or showed stripes were considered inferior." I believe this discrimination against the line-backed jack is outdated when it comes to the breeding of the saddle mule. Many of the best of the modern saddle mules have been sired by line-backed jacks, and in fact, many people prefer these mules with stripes. The selection pressure against the stripe comes from a time when the most compelling reason to breed jackstock was to produce the draft mule. If this is your "cup of tea,” it is logical to breed jacks with sorrel color, white manes and tails, heavy bone, big flat feet, and a longer head. None of the above are necessary traits for saddle mules. Please understand, I love and admire the big old-time Mammoth stock and its history. There will always be a need for this stock and the mules that they sire, but we won't be needing them to sire riding mules.

As for this matter of color preference, it nearly always follows a trend or fad. An example of this can be found in the book A History of American Jacks and Mules by Frank C. Mills. Mr. Mills' first venture into the jackstock business was the purchase of two jennets; one of these was a young blue line-back jennet named Ball's Choice. Mills believed her to be the best conformed jennet he ever owned. When shown at the Kansas State Fair in 1914, she was placed third in class. Another of the Mills' jennets, a black of lesser quality, was placed second. After the show, Mills asked the respected judge why this had happened; his reply was, "You are right about her with this exception. It would be a folly for a judge to place a first prize or champion ribbon on any jack or jennet except one that is black with white points. You may live to see the day it will be done...I doubt if I will."

Mr. Mills goes on to mention the breeder of the jennet Ball's Choice, H.R. Ball of Alden, Kansas. The jacks bred by Mr. Ball had a reputation for siring outstanding mules. Mills states, "Most of the Ball jacks and jennets I saw were either of gray or blue color and undoubtedly of Andalusian origin." I personally believe Maltese breeding would be more likely as I am told that the Andalusian was more often a true gray and not line-backed blue. Mills also states, "Most of his jacks and jennets were referred to as Ball's jacks or jennets. During that time, gray or blue colored jacks did not bring prices comparable to the black jacks or jennets with white points. However, the mules sired by his jacks brought prices often times higher than mules sired by black jacks. The color of a mule made little difference to the farmer who worked him."

Mills also mentions a man named Sam Whitfield from Sterling, Kansas. In 1909, Whitfield went to Missouri where he bought the jack Ben Franklin and another jack. Ben Franklin was a dark blue, almost brown in color, the other was a large jack, very light blue or Maltese in color. Because of their color, he bought them at a lower price. Both of these jacks sired outstanding mules.

It amazes me that a jack capable of siring superior mules was thought to be inferior because of his color.

In the Mammoth Jackstock Handbook that I mentioned earlier, breeders are cautioned, "Careful records and careful selective breeding with culling of stock of inferior height and weight are the weapons of the Mammoth jack breeder against the constant attempts of nature to throw back to the ancestral wild ass height and weight and color."

This belief that a jack with a stripe should be avoided at all costs seems to be standard among most of the older breeders. I recall once showing a picture of Texas Scooter, a jack that I owned at that time, to a well-known jack breeder that I much admired. He informed me that Scooter looked the part of an excellent saddle-type jack, but that he would be of no value to sire jackstock because of his stripe.

After much consideration, I believe that the dun line-backed color must originate from Maltese jackstock, and possibly the common Mexican burro. In the case of the burro, it is more than likely to have descended also from Spanish and Maltese stock. There were also some line-backed jacks imported from Italy at the peak of the import market, but these were of poor quality and seldom used in the development of American stock.

In 1985, I received a letter from Gilbert Jones of Medicine Springs Ranch in Oklahoma. Mr. Jones was a founder of the Southwest Spanish Mustang Registry, as well as a breeder of the so-called Spanish mule from these mustang mares. He was a great source of information about the jacks used in the early 1900s. He wrote, "As to the Spanish jack and burro. There is quite a difference, I think. But they are all lumped into the same category nowadays. And no doubt among the B.L.M. wild burros are some with Spanish blood, as in certain areas some of these so-called burros will weigh 800 pounds or more.

In the area I grew up on Llano-staked plains, practically all jacks were Spanish, commonly called Maltese, and several of our neighbors had jacks and some, several jacks. Very few pure mustang mares existed then, 1920, most mares were part Thoroughbred or Steeldust, so was consequently up to 1000 pounds in size, and when bred to these 12 and 13 hand jacks, the mules would reach 1000 pounds or better. Most of these mules went south for southern cotton farmers.

Gray or gruella was a popular color years ago, and if you read the history of Spanish jacks since George Washington, the beginning of Mammoth jacks, they was quite tall and many come blue. Then the craze for black with white points took the day, until the red sorrel mule became popular.

I have noticed all my 80 years among jacks, blue jacks was by far the fastest breeders, where the Mammoth was usually very slow to serve mares. Of course there are exceptions. I have seen very few Mammoths that would breed out on the range, where the Spanish jack worked like a stud horse."

Mr. Jones, as I do, felt that the larger and more refined line-backed jacks were of Maltese origin and descent. This line-back gene must be very strong or dominant, because in spite of an all-out effort to eliminate it, it still crops up to this day. The best definition of the Maltese jack that I was able to find comes from the S.J.J.R. Handbook. The following is a summary of that description:

It is believed that the Maltese jack is of Arabian origin. They are the smallest of the breeds of asses used to formulate the American Mammoth jack. They were seldom taller than 14-1/2 hands. The pure Maltese was black, brown or blue in color, but in a herd of them brown will dominate. Their legs are slender, resembling those of a Thoroughbred horse, with very good feet and large shiny hooves. They were a very game animal with a fiery disposition. The Maltese jack was originally admired for its well-balanced body and style, but because of its height and small bones, it was found to be unsuitable for U.S. Mammoth breeders.

During the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, the Maltese was the only breed of jack in the U.S. that was known by its breed name. The others were grouped together and called "Spanish Asses."

This and every other mention of the Maltese jack that I have read, leads me to believe that they possessed a lot of traits that we value today in a saddle mule jack. The only problem with this is in the fact that the Maltese jack no longer exists. We are left with only the throw-back and the burro. The discrimination against the dun line-back color was so intense that it is nearly lost in today's larger stock. I read with interest, Max Harsha's comments in the March 1995 issue of Western Mule magazine. Max believes that the saddle mule breeder needs a mixture of desert burro and Mammoth or "Catalonian" blood. Without some of this larger blood, the mules produced won't get enough size, and disposition can often be a problem. I have seen some excellent mules from the smaller line-back jacks, but today's market for saddle mules seems to prefer the ones around 15 hands. For this reason, the blend that Max talks about would seem to be the answer, provided that quality, style, and athletic ability can be maintained. The better saddle mule jacks that I have seen would fit into this category.

I think that today's jackstock breeders need to work toward the development of a saddle-type jack. I don't believe that one type or style of jack can sire both good draft and good saddle mules. The two types are just too different. Until we can get past some of the small issues, such as color, I don't think we can expect much improvement.

The jack that I am using now is a mixture of line-back and mammoth breeding. His dam is one of, if not the best, line-back jennets I have seen. He was foaled in September 1993, and presently stands over 57 inches at 2-1/2 years. I would expect him to sire the 15-hand mules that I like. In order to produce more of this type of stock I would like to find a nice line-backed jennet to cross with him.

As for the best color of jackstock, a good old-time jack man once told me, "There is no bad color on a really good jack."